The Unbroken Line: How the Comédie-Française Defies Time

La Comédie-Française has stood at the heart of French culture for over three centuries, a beacon of art that seems immune to the passage of time. It is a rare exception to the natural order of things. As Charlie Munger, the pragmatic philosopher of business, once noted about the harsh reality of evolution: “in the long run, all individuals die and all species die.” This rule usually applies ruthlessly to human organizations, yet the House of Molière has defied this evolutionary mandate. It has withstood invasions, civil wars, revolutions, and two world wars, emerging not as a fossil, but as a vibrant institution, constantly reinventing itself to remain a timeless force of artistic vitality.

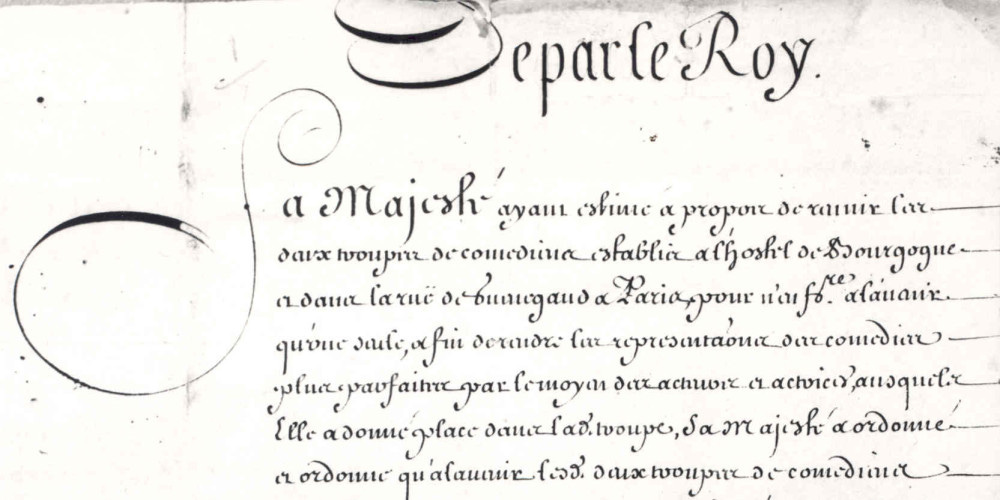

To the passerby, the Comédie-Française is merely a building—the Salle Richelieu—standing somewhat inauspiciously next to the Palais-Royal. Yet, the Comédie-Française is not a place; it is a people. Born from the iron will of the Sun King, Louis XIV, who in 1680 issued a lettre de cachet forcing the fusion of Paris’s rival troupes—the Hôtel de Bourgogne and the Théâtre de Guénégaud—it was granted a monopoly on the spoken word. While the company has shifted venues, finally claiming the Salle Richelieu in 1799, the entity itself has remained unbroken. It is a continuous performance that has outlasted kings and emperors, standing today as the oldest active theatre troupe in the world.

Central to this continuity is the Repertoire, a colossal, library of over 3,000 plays. Unique in France, the troupe practices alternance (alternating repertory), meaning they perform different plays in rotation rather than long consecutive runs of a single show. This demanding rhythm transforms the actors into intellectual athletes, capable of performing Molière one night and a contemporary premiere the next.

While Molière remains the “Patron”—his works have been performed more than 35,000 times—he is far from alone. The Repertoire rests on a foundation of other French giants: the noble tragedies of Corneille and Racine, the intricate romantic games of Marivaux and Musset, and the manic clockwork farces of Feydeau. Yet, it is an ever-expanding organism, constantly absorbing new writers—from Victor Hugo and Chekhov to contemporary voices—to ensure the conversation between the 17th century and the modern day continues.

Governance and Structure

The internal organization of the Comédie-Française is distinct among world theatres, operating as a self-governing society under the motto Simul et Singulis (Together and Apart). The state appoints an Administrateur général to oversee the institution, but the core hierarchy is determined by the actors. New actors join as pensionnaires, or salaried employees. After a period of proven service, they may be elected by the committee to become sociétaires. These members function as shareholders who hold a financial stake in the society, vote on the budget, and influence artistic decisions.

This unique profit-sharing model traces back to Molière’s own troupe, where he established a similar economic structure; notably, Molière paid himself only two shares—one as an actor and one as the playwright—double what other members received.

Permanent Venues and Current Expansion

While the Comédie-Française is historically anchored to the Salle Richelieu, the troupe performs across a wide network of stages. This season is unique due to programmed renovations at the Salle Richelieu. With the historic theatre scheduled to close for works on January 16, 2026, the troupe has organized an extensive “Hors les Murs” (Outside the Walls) schedule starting in mid-January. The complete list of venues currently utilized includes the two other permanent stages: the Théâtre du Vieux-Colombier in Saint-Germain-des-Prés and the Studio-Théâtre in the Carrousel du Louvre. Additionally, the 2025-2026 season utilizes fixed points at the Théâtre de la Porte Saint-Martin and the Théâtre du Petit Saint-Martin, alongside partner theatres including the Théâtre du Rond-Point, Odéon-Théâtre de l’Europe, Théâtre Montparnasse, Théâtre Nanterre-Amandiers, Le 13ème Art, the Grande Halle de la Villette, and the Théâtre du Châtelet.

The Legend of Molière’s Chair

The troupe is widely known as La Maison de Molière, a title that honors its spiritual father even though Molière died seven years before the company was officially founded. The most significant artifact linking the playwright to the institution is the armchair he used during the fourth performance of Le Malade imaginaire on February 17, 1673. A persistent myth suggests that Molière died on stage in this chair. Historical records clarify that while he suffered a violent coughing fit and a pulmonary hemorrhage while seated in it during the performance, he managed to finish the play. He was subsequently transported to his home on the Rue de Richelieu, where he died later that night. The chair is preserved today in the public foyer of the theatre, displayed behind glass rather than used on stage.

Recent Performance of Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme

The vitality of the current ensemble is evident in their recent production of Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme, directed by Valérie Lesort and Christian Hecq. The performance strictly adheres to Molière’s text while incorporating distinct modern staging elements. The production utilizes Balkan-style live music and sophisticated choreography to heighten the farce, particularly during the “Turkish ceremony” sequence. The costumes are designed with exaggerated proportions and bright colors, enhancing the comedic absurdity of the characters. This approach demonstrates the troupe’s ability to maintain the integrity of a 17th-century classic while delivering high-energy entertainment that appeals to contemporary sensibilities.

Ticket Pricing and Accessibility

As a state theatre, the Comédie-Française operates under a mandate of public service, which is reflected in its pricing strategy. Tickets are significantly more affordable than those for comparable productions in commercial theatre districts like Broadway or the West End. The institution maintains a specific tradition known as the “Petit Bureau,” where a designated number of reduced-visibility seats are sold one hour before each performance at the Salle Richelieu for five euros. This policy ensures that financial status is not a barrier to entry and that the French theatrical repertoire remains accessible to the general public.

In an effort to expand its reach beyond Francophone audiences, the Comédie-Française has implemented new technology to overcome language barriers. The theatre now offers augmented reality glasses. Unlike traditional surtitles projected above the stage, which force the viewer to look away from the action, these glasses project synchronized English subtitles directly onto the user’s lenses. This system allows international visitors to follow the dialogue in real-time without losing visual contact with the actors’ performances.

A Look Behind the Curtain

For those wishing to understand the intricate human machinery that powers this institution, the documentary La Comédie-Française ou L’Amour joué (1996) by Frederick Wiseman offers an unparalleled glimpse behind the scenes. Known for his observational cinema style, Wiseman spent weeks filming the daily life of the troupe without narration or interviews. The film captures the exhaustion of rehearsals, the tension of administrative meetings, and the sheer dedication required to keep such a massive organization running.

A Personal Note of Admiration

It is rare to find an institution that achieves such excellence while remaining so unpretentious and egalitarian. They are not merely preserving a dusty history; they are keeping it vibrantly alive for us. Witnessing their dedication to welcoming new audiences—whether through affordable tickets, the exceptional courtesy of their staff, or innovative technology—reminds me why art matters. It belongs to all of us, and the Comédie-Française is the most incredible steward of this shared heritage.