The Bergman Tetralogy: How One Man Lived Four Filmmaking Lives

Ingmar Bergman did not inhabit a single career; he lived through a series of distinct cinematic lifetimes. His body of work is so expansive and transformational that any one of his major stylistic periods—ranging from medieval allegories to modern psychological breakdowns—could have served as a complete, hall-of-fame legacy for a lesser director. These four architectural pillars of filmmaking represent a profound trajectory, moving from the grand, externalized search for faith toward the total, internal disintegration of the human psyche.

Underpinning these stylistic shifts was a trio of core influences that remained constant throughout his life. His vision was forged by the psychological “chamber” drama of August Strindberg, the haunting religious iconography of his strict Lutheran upbringing, and the volatile enmeshment of his personal and professional relationships on the island of Fårö.

Together, these forces allowed Bergman to move beyond traditional filmmaking to create what feels less like a single filmography and more like an entire school of world cinema.

Pillar I: The Allegorical Epics (1950s)

If Bergman had stopped at the end of the 1950s, his place in history would be secured as the master of the “modernist allegory.” During this era, he took the abstract fears of the post-war world—nuclear annihilation, the silence of God, and the weight of mortality—and transformed them into grand, visual poetry. The Seventh Seal (1957) and Wild Strawberries (1957) are the twin peaks of this career. In these films, characters embark on literal journeys that are actually spiritual odysseys. This period is marked by high-contrast black-and-white cinematography and a theatrical sense of staging that made metaphysical questions feel as urgent as a thriller.

Pillar II: The Chamber Works and the Trilogy of Faith (Early 1960s)

In the early 1960s, Bergman reinvented himself by shrinking his canvas to a microscopic size. This “second career” focused on the “Trilogy of Faith”—Through a Glass Darkly, Winter Light, and The Silence. Moving away from the grand symbols of knights and Death, he focused on the faces of people trapped in small rooms. This era pioneered the “chamber film” style, characterized by long, unflinching close-ups and the agonizing examination of how people use language to bridge the gap between their souls. It was a career dedicated to the quiet, devastating realization that God might not just be silent, but absent.

Pillar III: The Modernist Disintegration (Late 1960s - Early 1970s)

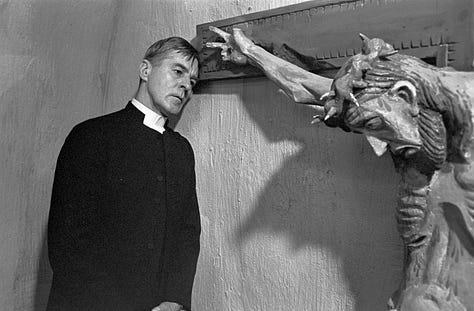

The third pillar of Bergman’s life was his most radical. In films like Persona (1966), Hour of the Wolf (1968), and Shame (1968), he moved beyond spiritual doubt and into the total collapse of the human identity. This era could be viewed as a career in psychological horror and avant-garde exploration. He experimented with the very fabric of film—showing the celluloid burning or breaking the fourth wall—to mirror the way his characters’ psyches were fracturing. This period, largely set on the barren shores of Fårö, explored the idea that the “self” is merely a mask, and that beneath it lies a terrifying, shared void.

Pillar IV: The Domestic Epics and the Final Summation (1970s - 1980s)

In his final major phase, Bergman synthesized his career-long obsessions into grand, humanistic tapestries. This “fourth career” was characterized by a move toward color and a novelistic depth of character. Scenes from a Marriage (1973) and Cries and Whispers (1972) turned the clinical precision of his earlier work toward the brutal reality of domestic life, while Fanny and Alexander (1982) served as a definitive closing statement. This era saw a director who had moved through allegory, faith, and madness to arrive at a place of reconciliation, viewing the world through a lens that was both unflinchingly honest and extremely personal.

The Crucible of Influence

Bergman’s vision was forged in a crucible of three primary forces: the psychological “chamber” drama of August Strindberg, the haunting religious iconography of his Lutheran upbringing, and the volatile, often blurred boundaries between his professional and private lives.

The most significant ghost haunting his work was the playwright August Strindberg. Bergman found in him a soulmate who shared a preoccupation with the “inferno” of domestic life and the psychological warfare between men and women. He adopted Strindberg’s chamber play structure—stripped-down stories focusing on intense conflict within a confined space—which allowed him to turn the camera into a microscope. Complementing this was the religious shadow of his childhood. As the son of a strict Lutheran chaplain, Bergman spent his youth in country churches mesmerized by medieval murals of demons, angels, and the personification of Death. These “bibles for the illiterate” taught him that the spiritual world was a tangible, terrifying reality, a belief most vividly realized in the iconic imagery of The Seventh Seal.

Beyond these aesthetic roots, his work was inseparable from the “Fårö Circle”—a stock company of actors who became his extended family. The dynamics were often fraught with the complexities of romantic and professional intimacy. Bergman required an invasive level of vulnerability from his performers, and the lines between the director’s chair and the private bedroom were famously blurred, particularly in his relationships with muses like Harriet Andersson, Bibi Andersson, and Liv Ullmann.

His status as a national icon was also shaped by his complex relationship with Sweden itself. Despite putting the nation on the global cinematic map, his career was interrupted by a traumatic “German hiatus” in 1976. Following an interrogation for alleged income tax evasion, he fled to Munich in self-imposed exile. While his work in Germany reflected his displacement and paranoia, his eventual return to Sweden to film Fanny and Alexander served as a grand reconciliation, cementing his legacy as the nation’s greatest cultural ambassador.

Conclusion: An Infinite Legacy

The four distinct career stages of Ingmar Bergman’s filmography are even more awe-inspiring when put into the context of his turbulent personal life and his work in other mediums. Alongside his sixty films, Bergman directed over 170 stage plays, dozens of television productions, and numerous radio plays, maintaining a work ethic that seemed almost superhuman. He achieved this monumental body of work while fathering nine children across several marriages, battling lifelong intestinal ailments that often required surgery, and grappling with his own profound psychological demons. Never has a single figure done so much to place their country and its language so firmly upon the cultural map of the world as Bergman did for Sweden.

While history has certainly produced famously prolific creators, Telemann composed over 3,000 compositions, or Isaac Asimov, who authored more than 500 books, it is rare to encounter such immense volume coupled with the rigorous intellectual depth and constant stylistic evolution that Bergman achieved. Many masters eventually falter or become repetitive in their later years; look at Picasso’s late-period peace doves.

Bergman managed to have four careers in a single lifetime; for those of us searching for a second act, we can truly appreciate the immensity of his achievement.