Gustave Caillebotte: A Legacy Beyond Collecting Impressionist Masterpieces

The recent global retrospective dedicated to Gustave Caillebotte, which began its journey at the Musée d’Orsay before traveling to the J. Paul Getty Museum and the Art Institute of Chicago, has finally allowed the artist to step out from the shadow of his reputation as a mere financier. For over a century, Caillebotte was remembered primarily as the generous benefactor who funded the Impressionists, but this recent exhibition highlight an artist in his own right and not just a patron for other well-known artists.

By examining his specific approach to masculinity, his profound fraternal bonds, and his pivotal stewardship of Manet’s legacy, we see an artist who documented the changing ethos of the 19th century while leaving an indelible mark upon it.

The Monumental Vision of Paris

For most the name Caillebotte evokes one iconic work, Paris Street; Rainy Day. Housed at The Art Institute of Chicago, this monumental canvas captures the intersection of the Place de Dublin with a startling, almost cinematic clarity. While his contemporaries might have used loose brushstrokes to suggest the atmosphere of rain, Caillebotte used sharp lines and a dramatic, wide-angle perspective to emphasize the vastness and anonymity of Baron Haussmann’s newly redesigned Paris.

Gender, Family, and the Psychological Interior

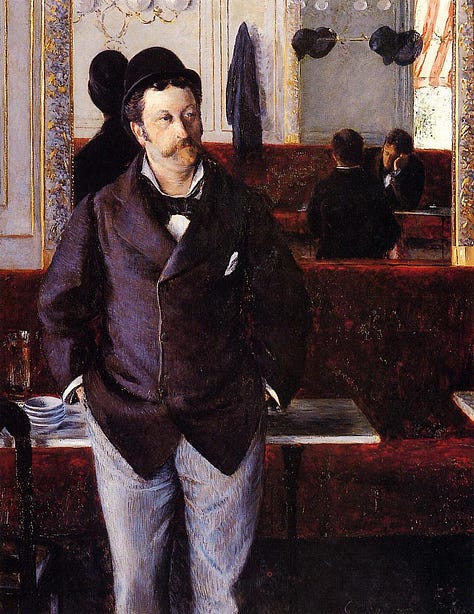

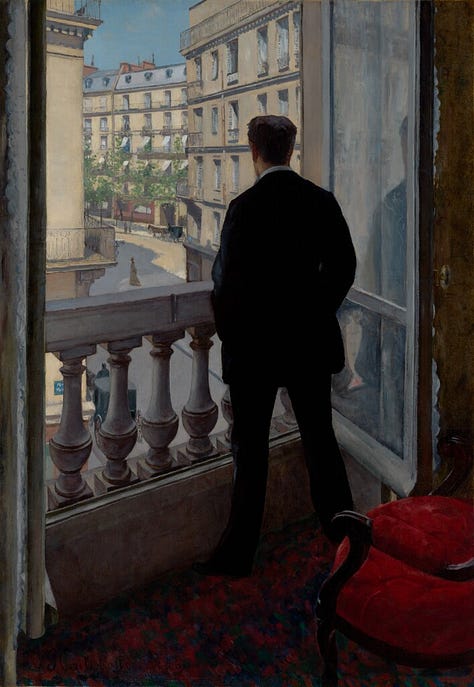

The role of the man within this Haussmannized landscape is one of both mastery and alienation. In Caillebotte’s Paris, the masculine figure is the quintessential urban stroller (flâneur)—a detached observer who navigates the rigid, disciplined geometry of the boulevards with a calculated anonymity.

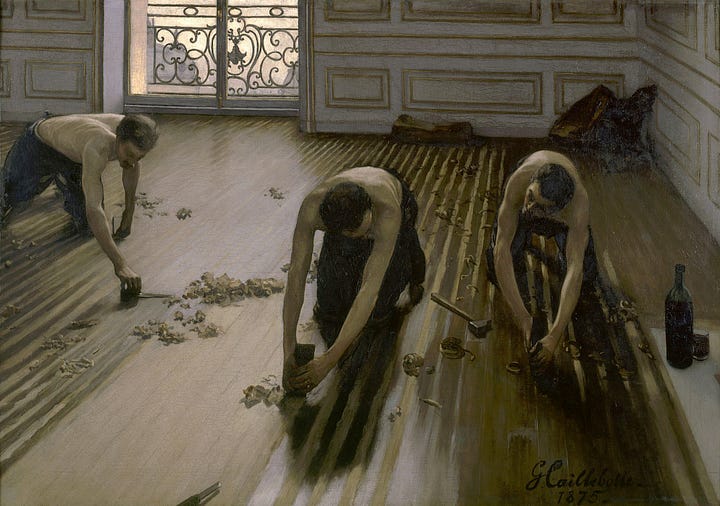

As the exhibit demonstrates, Caillebotte’s fascination with manliness and the male form was radical for its time, moving away from the soft, dappled light of his peers toward a gritty, photographic realism that redefined masculinity as a site of modern leisure and quiet, domestic introspection.

He focused his gaze on his own social circle—most notably his brother Martial and their close friends—capturing them as active participants in the new Parisian life. Whether depicting them in a rowing scull on the Yerres, strolling the expansive new boulevards as flâneurs, or concentrated on a quiet game of cards or billiards, Caillebotte presented the male body with a startling, contemporary directness that eschewed classical idealization. This investigation into the masculine world was deeply intertwined with his own personal history, specifically the profound loss of his brother René in 1876. This tragedy solidified an intense, lifelong bond with Martial, who became Gustave’s most frequent subject and muse. By painting Martial in the intimate, quiet spaces of their shared home—often shown absorbed in music or literature—Caillebotte provided a rare, vulnerable glimpse into the private domestic life of men during the Belle Époque.

These portraits reflect a shared grief and a fraternal closeness that defined much of Gustave’s adult life, during which the brothers remained bachelor companions.

Influence on Future Generations of Filmmakers

The avant-garde nature of Caillebotte’s compositions—his use of plunging perspectives, high vantage points, and the “cropped” framing of his subjects—anticipated the birth of cinema and continues to resonate with filmmakers and visual artists. I found a striking example of this long-reaching influence in Sergei Parajanov’s Kyiv Frescoes (1966). Though separated by nearly a century and vastly different cultural contexts, both Caillebotte and Parajanov share a fascination with the “tableau” and the psychological weight of objects within a frame.

Most notably, Parajanov literally recreates the visual language of The Floor Planers within the dreamlike, non-narrative structure of Kyiv Frescoes. In the film, he meticulously stages figures in a way that mirrors Caillebotte’s plunging floorboards and the rhythmic, physical geometry of the laborers.

While the wine bottle from the original painting is replaced by a jug of water, there is no doubt about who Parajanov is visually quoting.

The Guardian of Manet and the Impressionist Legacy

Finally, Caillebotte’s legacy is inextricably linked to his role as a guardian of French art, most notably through his ownership and protection of Édouard Manet’s work. Caillebotte was one of the few who recognized that Manet was the true bridge to modernity. Following Manet’s death, Caillebotte was instrumental in the campaign to purchase the controversial Olympia for the French state. He understood that for Impressionism to survive, it needed a place in the national museums. His massive bequest of 68 paintings to the state—which included many of his own works alongside those of Manet, Monet, and Renoir—faced significant backlash from the academic establishment, yet it eventually formed the very heart of the Musée d’Orsay’s collection.

Conclusion: An Artist of the Highest Order

Gustave Caillebotte stands today as an artist of the highest order, whose contributions to the history of art extend far beyond his checkbook. While history initially cast him as the humble guardian of his friends’ masterpieces, the recent global retrospectives have illuminated an original creator and a source of inspiration for future artists.

You can virtually visit the exhibit in this video produced by the Musée d'Orsay. While this represents a style of art history and curatorship that diverges from my own perspective (see Power of Art), the video at least allows you to see some incredible pieces that are not easily found on Google.