Édouard Manet’s Enigmatic Masterpiece: A Bar at the Folies-Bergère

How to Spend Three Hours at the Courtauld Gallery to Look at Just One Painting

Édouard Manet’s final major work, A Bar at the Folies-Bergère (1882), remains one of the most compelling and perplexing paintings in the history of art. More than just a lively depiction of Parisian nightlife, the canvas is a meticulously constructed visual riddle that has captivated and frustrated viewers and critics for over a century. The central enigma lies in the reflection of the blonde barmaid, Suzon, and the gentleman client, whose presence in the mirror seems to violate the basic laws of perspective and optics.

The composition presents Suzon standing squarely before us, her expression distant and world-weary, framed by a lavish display of liquor bottles, fruit, and flowers. Directly behind her is a massive mirror, which should, in theory, show her back and our own reflection. Instead, the reflection of Suzon is displaced significantly to the right, leaning slightly toward a shadowy gentleman whose back is turned to the viewer. This distortion of reality has spawned numerous theories attempting to reconcile the visual evidence with logical space:

The Subjective Viewer: One prominent explanation suggests that Manet deliberately distorted the perspective so that the viewer is meant to occupy the physical space of the gentleman in the reflection. In this reading, the scene is painted from a slightly offset position, requiring the viewer to stand exactly where the client is reflected in the mirror for the reflection to appear as it does. The distortion is thus a conscious device to make the observer an active participant in the scene.

A Dazed Encounter: Other interpretations delve into the psychological state of the barmaid. The painting captures a moment of emotional detachment; Suzon appears physically present but mentally elsewhere. The skewed reflection could symbolize this psychological dissonance, suggesting that the reflected image is not an objective reality but a fleeting, perhaps imagined, memory or a wishful projection of the imminent, impersonal transaction.

The Temporal Displacement: A more fanciful idea posits a subtle temporal shift or “time travel” within the scene. The reflection is not instantaneous but slightly delayed or remembered, offering a glimpse of the moment immediately preceding or following the encounter.

However, as we keenly observe, the enigma extends far beyond the barmaid and the gentleman. The sheer depth of the painting’s ambiguity lies in how much of the scene is warped and manipulated, bordering on the principles of early Cubism in its deconstruction of spatial coherence. It is not only the figures whose reflections are skewed, but the entire arrangement—the displacement of the liquor bottles on the left, which appear in the reflection at an impossible angle; the jarring collision of the foreground counter with the background space; and the deep, endless perspective itself, which seems to pull the viewer into an unsettling, floating space. This manipulation of multiple viewpoints within a single frame creates a sense of spatial ambiguity that transcends simple perspective error, suggesting a deliberate attempt by Manet to capture the fragmented, disorienting experience of modern life and spectacle.

What the Courtauld Gallery Wants Us to Know

The Courtauld Gallery plaque, where A Bar at the Folies-Bergère is housed, reads the following:

At one of the bars in the Folies-Bergere - a popular Parisian music hall - wine, champagne and British Bass beer with its red triangle logo await customers. A fashionable crowd mingles on the balcony. The legs and green boots of a trapeze artist in the upper left hint at the exciting musical and circus acts entertaining the audience. This animated background is in fact a reflection in the large gold-framed mirror, which projects it into the viewer’s own space.

Manet made sketches on-site but painted this work entirely in his studio, where a barmaid named Suzon came to pose. She is the painting’s still centre. Her enigmatic expression is unsettling, especially as she appears to be interacting with a male customer. Ignoring normal perspective, Manet shifted their reflection to the right. The bottles on the left are similarly misaligned in the mirror. This play of reflections emphasises the disorientating atmosphere of the Folies-Bergère. In this work, Manet created a complex and absorbing composition that is considered one of the iconic paintings of modern life.

An adequate explanation, to be sure, but somehow deeply unsatisfactory.

Contemporary Commentary

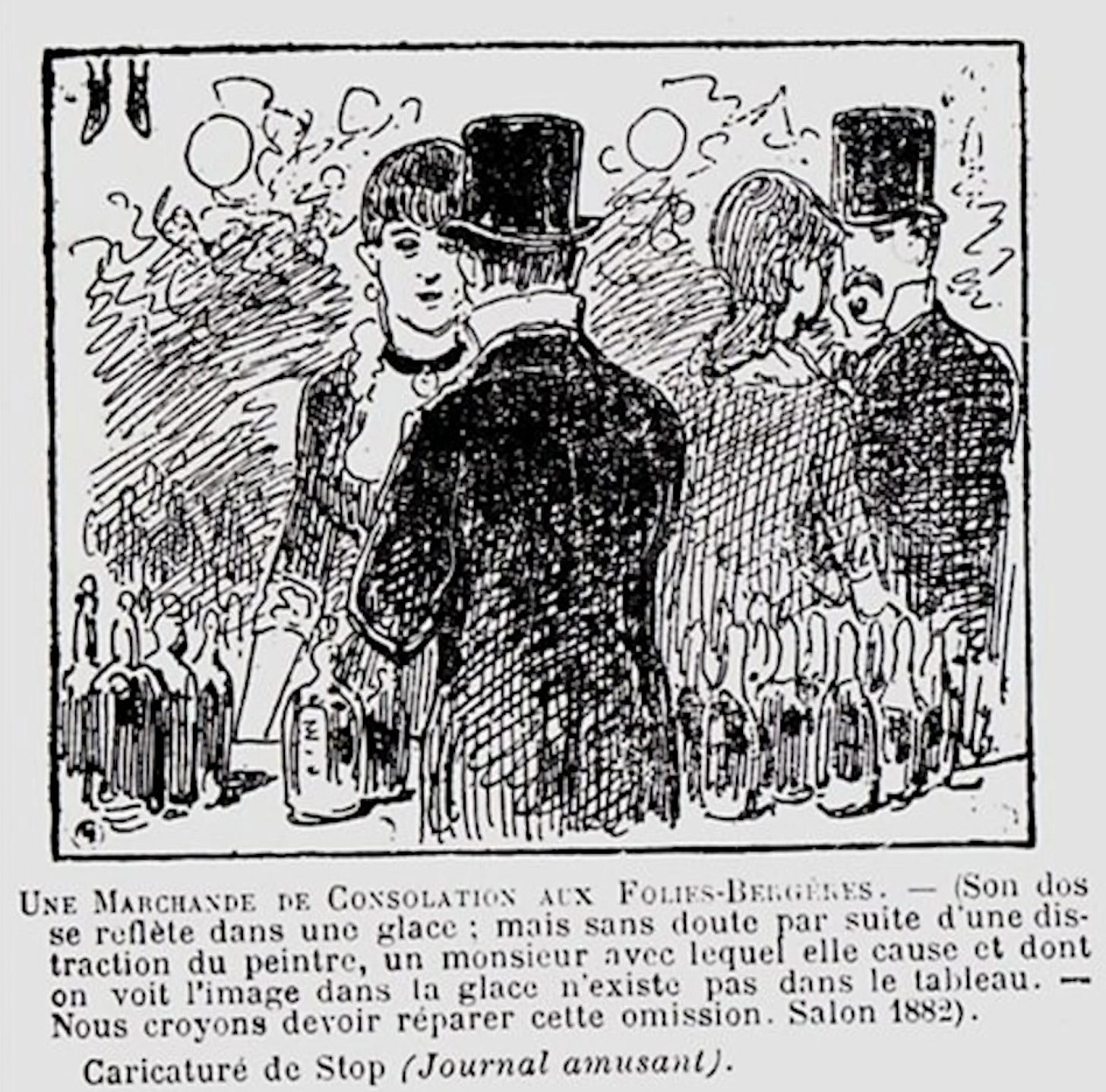

The spatial and optical inconsistencies were so immediately apparent upon its exhibition at the 1882 Salon that they became the subject of contemporary satire. Caricaturists, assuming the distortions were simply an error or an “omission” by the ailing Manet, set out to “correct” the composition. Titled Une Marchande De Consolation Aux Folies-Bergères (A Seller of Consolation at the Folies-Bergère) in the Journal Amusant, is a prime example of this reaction. The caption notes that the barmaid’s back is reflected in a mirror, “but doubtless as a result of a distraction of the painter, a gentleman with whom she is speaking and whose image is seen in the mirror does not exist in the picture. We think we can repair this omission”.

This initial, humorous attempt to correct the painting underscores just how unsettling and revolutionary Manet’s manipulation of perspective was to his contemporary audience, who struggled to accept the visual riddle as an intentional artistic choice.

Notice the cartoonist achieves a darkly humorous effect by omitting the trapeze apparatus, making the dangling legs appear as if they belong to someone who has hanged themselves, transforming Manet’s vibrant bar scene into a macabre gag.

Then, There is Manet’s Spanish Fascination

Édouard Manet’s profound admiration for the Spanish Old Masters, particularly Diego Velázquez, forms the foundation of his so-called Spanish Period in the 1860s. This period was characterized by a distinct shift toward Spanish themes, figures, and, most importantly, Velázquez’s innovative painting techniques. Manet’s fascination began even before his 1865 trip to Spain and the Prado, demonstrated by earlier works like The Spanish Singer (1860), which brought him his first Salon success, and The Spanish Ballet (1862). These paintings employed dark, flat backgrounds, bold outlines, and a focus on costumed figures that reflected the French vogue for Spanish culture, but also Manet’s initial grasp of the Spanish Baroque style. Upon seeing Velázquez’s work in the Prado, Manet was overcome, famously declaring him “the painter of painters” and the greatest artist who ever lived. He was captivated by the Spanish master’s bold, fluid brushwork, his sophisticated use of light and dark (tenebrism), and his commitment to a stark, unidealized Realism that offered a powerful alternative to the academic traditions of the time. Paintings like The Fifer and The Philosopher (both 1866) are direct descendants of this encounter, stripping away excess detail to focus on isolated, powerful figures against plain backgrounds, echoing Velázquez’s technique.

The connection between Velázquez’s masterpiece, Las Meninas (1656), and Manet’s oeuvre is plausible, leading many critics to suggest that Manet’s final major work is, in effect, Manet’s Las Meninas. Both paintings are complex, enigmatic masterpieces that transcend simple portraiture or genre scenes to become profound meditations on the nature of painting, space, and the act of seeing. Las Meninas famously challenges the viewer by placing the subjects (King Philip IV and Queen Mariana) outside the painted frame, visible only as a reflection in a small mirror, while the artist, Velázquez, stands in the foreground, asserting the nobility of painting.

Manet, in turn, takes the aesthetic of reflection, the shifting of perspective, and the blurring of the boundary between the viewer and the viewed, and transports it to modern Parisian life. By replacing the royal retinue with the world-weary barmaid and the music-hall crowd, Manet created a work that serves as a self-reflexive manifesto for Modern art, shifting the focus from the royal court to the complexities of urban, modern experience.

Enough Art History! What Can We Say About Suzon?

Suzon, the barmaid at the centre of Manet’s painting, is characterized by a striking tension between her physical presence and her internal distance, inviting multiple readings. Her features are often noted as being rather rustic, lacking the refinement of the Parisian bourgeoisie, leading to the interpretation that she may have immigrated from the French provinces, perhaps Brittany or Provence, and is struggling to adjust to the direct, often harsh, social dynamics of the capital. The source of her downcast and somewhat flushed expression remains a key ambiguity; while some interpret it as a reaction to a man’s proposition—perhaps the very gentleman whose reflection stands beside hers—others see it as simply the effect of the heat and exhausting pace of the crowded bar. Furthermore, her presentation includes a deliberate act of modesty: she covers her décolletage with a corsage (a small bouquet of flowers), suggesting a layer of prudishness or a desire for self-protection that contrasts sharply with the overtly sexualized atmosphere of the Folies-Bergère and her public-facing role.

My Final Analysis: Manet’s Optical and Social Nuances

Manet’s A Bar at the Folies-Bergère operates on multiple interpretive levels, using formal decisions to analyze the psychological fabric of modern life, echoing the intense realism found in the novels of Émile Zola. The central figure’s direct, photographic gaze is a technique Manet used to implicate the viewer, forcing them to confront their role as a consumer and spectator of the working woman. This gaze presents her with the stoicism and weary professionalism characteristic of Zola’s personas navigating the hard realities of service and commerce, as depicted in the series Les Rougon-Macquart.

The painter employs perspective distortions not through error, but as a deliberate philosophical trick intended to challenge the viewer’s perception of objective reality. The startling misalignment of the barmaid and her reflection makes the mirror a device that signifies something beyond mere sight, suggesting that the scene’s spatial logic is governed by subjective experience rather than strict optical rules. By positioning the viewer precisely where the male customer stands, Manet compels the spectator to become a direct participant in the social exchange under scrutiny—an incisive examination of class dynamics and the anonymity of city life, characteristic of Zola’s stark social commentary.

Finally, Manet elevates contemporary life by presenting the barmaid as a classical figure—a modern Venus—displayed in the commercial “temple” of the Folies-Bergère. This pairing of timeless form with a transient, commercial setting affirms that the reality of the 19th-century urban scene is a subject for high art, making the work a profound meditation on the gaze, reality, and the spectacle of urban commerce.

Manet’s visual departures are thus best understood not as precursors to 20th-century existential despair (Camus, Sartre, etc), but as a pictorial alignment with the immediate, unflinching social realism advocated by his contemporary and champion, Émile Zola.

Ultimately, the genius of the work lies in its enduring ambiguity, ensuring its constant relevance and initiating new dialogue about representation, class, and social dynamics—a masterful demonstration of the painting’s ability to “go viral” across his time and our own.