Bridging Minds and Mediums: How LLMs Can Revolutionize Artistic Collaboration

Adapting Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain, into a stage play using an LLM

The creation of art, particularly in complex projects like adapting a sprawling novel into a play, often involves intricate collaboration between diverse artistic minds. Visionaries, writers, designers, directors, and performers must align their interpretations, often leading to time-consuming discussions, misunderstandings, and creative bottlenecks. However, with the advent of advanced Large Language Models (LLMs), a powerful new tool emerges to streamline this collaborative process, fostering clearer communication and accelerating creative development.

Let’s take the challenging example of adapting Thomas Mann’s monumental novel, The Magic Mountain, into a stage play. (Wes Anderson, please don’t get any ideas! This work definitely will not benefit from symmetric set designs or deadpan)

This novel, rich in philosophical debate, psychological depth, and symbolic imagery, presents a formidable task for any adaptation team.

The Challenge of The Magic Mountain Adaptation

The Magic Mountain is not a plot-driven narrative in the conventional sense. Its essence lies in:

Dense Intellectual Debates: The lengthy discussions between Settembrini and Naphta, central to the novel, need to be dramatized without becoming static or overly academic on stage.

Internal Monologue and Stream of Consciousness: Hans Castorp’s internal journey and observations are paramount, yet direct translation to dialogue is often clunky.

Symbolism and Allegory: The sanatorium itself, the characters, and events all carry layers of symbolic meaning that must be conveyed visually and textually.

The “Distorted Time” Element: The novel’s unique pacing, where seven years pass in a subjective blur, needs innovative theatrical representation.

Visualizing the Mundane and the Sublime: The everyday routine of the sanatorium juxtaposed with moments of profound realization (like the “Snow” chapter) requires careful artistic balance.

How an LLM Facilitates Collaboration: A Practical Playbook

An LLM can act as an intelligent assistant, a tireless brainstorming partner, and a central repository for creative iteration, making the collaborative journey smoother and more efficient. Here’s how:

Initial Brainstorming and Conceptualization (The “Outline”): Before a single line of script is written, an LLM can help the director and playwright align on the core vision. An LLM can quickly distill complex narratives into manageable chunks. See appendix at the end of the article for an example.

LLM’s Role: Generate scene summaries, identify key character arcs, propose thematic through-lines, and even suggest different structural approaches (e.g., linear vs. non-linear, focus on specific characters). This rapid prototyping allows the team to explore multiple high-level concepts quickly.

Benefit: Reduces initial friction, ensures everyone starts with a shared understanding of the narrative backbone, and provides a tangible document for discussion.

Visualizing the Narrative (The “Storyboard”): A playwright’s script often exists in a textual realm, while a director and set designer think in images. This is where the LLM’s image generation capability becomes transformative.

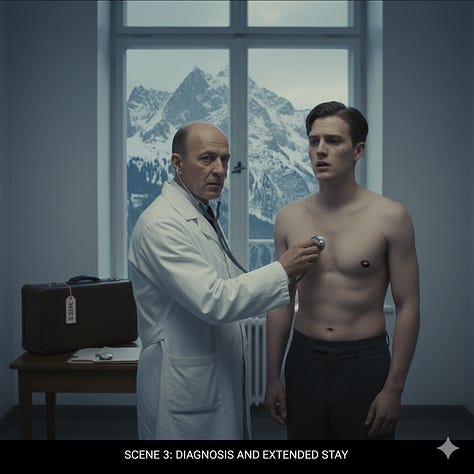

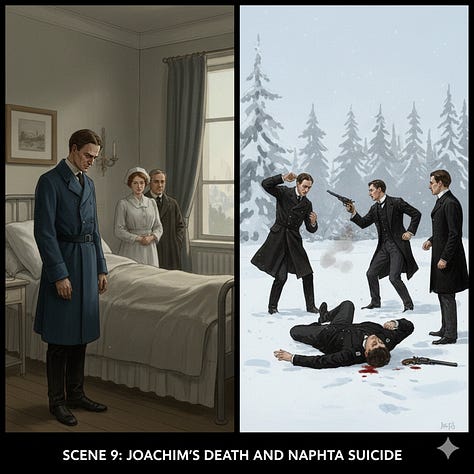

LLM’s Role: By taking scene descriptions from the script (or the generated outline) and converting them into visual storyboard images, the LLM provides a common visual language. For The Magic Mountain, imagining “Hans’s Arrival at Berghof Sanatorium” or “The Settembrini-Naphta Debates” as concrete images instantly bridges the gap between text and visual staging.

Benefit: Allows the director, set designer, costume designer, and lighting designer to see the playwright’s vision and offer feedback immediately. This iterative visual feedback loop drastically cuts down on misinterpretations and late-stage changes. “I envisioned the sanatorium as more imposing,” or “Can we try a darker, more claustrophobic feel for the debate scene?” become easy to communicate and visualize.

Character Development and Dialogue Prototyping: Bringing Mann’s complex characters to life requires nuanced understanding.

LLM’s Role: Generate character profiles based on the novel, suggest contemporary parallels, or even draft sample dialogues in the imagined voices of Settembrini, Naphta, or Hans. For instance, the LLM could craft a short exchange between Settembrini and Hans discussing the philosophical implications of a specific scientific discovery, helping the playwright find the right tone and cadence for their stage voices.

Benefit: Helps actors understand their roles better, assists the playwright in crafting authentic stage dialogue that honors the novel’s intellectual rigor, and provides directors with insights into character motivations.

Exploring Thematic Interpretations and Symbolism:The Magic Mountain is steeped in symbolism.

LLM’s Role: Ask the LLM to generate images or textual descriptions that embody specific symbolic elements – for example, what does “distorted time” look like on stage? How can the “Snow” vision be theatrically represented? The LLM can propose visual metaphors, soundscapes, or movement patterns.

Benefit: Inspires creative solutions for abstract concepts, ensuring the play’s deeper meanings resonate with the audience without explicit exposition.

Rehearsal and Blocking Assistance: Even during rehearsals, an LLM can be a resource.

LLM’s Role: Generate stage directions based on a text passage, suggest different blocking options for a scene, or even predict how a particular line might land with an audience based on various delivery styles.

Benefit: Helps directors and actors explore possibilities quickly, refining performances and stage presence.

Conclusion: The LLM as a Collaborative Amplifier

An LLM is not a replacement for human creativity, but an amplifier of it. By offloading repetitive tasks, providing instant visual and textual feedback, and serving as a boundless source of inspiration, LLMs can significantly reduce the friction points in artistic collaboration. For a monumental task like adapting The Magic Mountain, the ability to rapidly prototype ideas, visualize concepts, and iterate on nuanced details transforms what was once a slow, often frustrating process into a dynamic, fluid, and deeply collaborative journey.

Appendix

Major Scenes of The Magic Mountain

Hans Castorp’s Arrival at Berghof Sanatorium: Hans Castorp, a young engineer from the “flatlands,” travels to the Swiss Alps to visit his ailing cousin, Joachim Ziemssen, intending to stay for only three weeks. He is immediately struck by the strange, regulated life and the unsettling atmosphere of sickness and intellectual debate in the high-altitude sanatorium.

Initial Encounters and Routine: Hans is introduced to the daily routine of rest cures, lavish meals, and temperature-taking, quickly falling under the influence of the Italian humanist, Lodovico Settembrini. Settembrini attempts to serve as Hans’s mentor, warning him against the corrupting, deathly forces of the “Magic Mountain.”

Hans’s Diagnosis and Extended Stay: After experiencing a persistent fever, Dr. Behrens examines Hans and finds a “moist spot” on his lung, officially making him a patient and prolonging his intended three-week visit indefinitely. This diagnosis marks Hans’s full transition from a temporary visitor to a permanent resident, subject to the mountain’s distorted sense of time.

The Pursuit of Clawdia Chauchat (Walpurgis Night): Hans becomes intensely obsessed with the enigmatic Russian patient, Madame Clawdia Chauchat, an embodiment of physical desire and sensual dissolution. During the Mardi Gras celebration (”Walpurgis Night”), Hans finally confesses his love to her in French, leading to a brief, passionate encounter before she leaves the sanatorium.

The Settembrini-Naphta Debates: After Clawdia’s departure, a new, formidable intellectual rival for Hans’s soul appears in the form of Leo Naphta, a Jesuit intellectual advocating for radical, totalitarian, and anti-humanist ideas. The long, intense debates between the liberal Settembrini and the fanatical Naphta become a central focus, exploring the conflicting philosophies of pre-war Europe.

The “Snow” Chapter (Hans’s Vision): Hans goes out alone during a dangerous snowstorm and gets lost, experiencing a terrifying near-death vision of humanity and its dual nature of reason and dark passion. He concludes that for the sake of goodness and love, “man shall let death hold no sway over his thoughts,” resolving to hold on to his humanistic values.

Arrival of Mynheer Peeperkorn: The grand, Dionysian figure of Mynheer Pieter Peeperkorn, a wealthy Dutch coffee planter and Clawdia Chauchat’s new lover, arrives at the sanatorium, representing life’s sheer, inarticulate vitality. Peeperkorn’s presence inspires awe but also demonstrates the limitations of unmediated, purely sensual experience, leading to his dramatic, despairing suicide.

Joachim’s Death and Naphta’s Suicide: Hans’s steadfast cousin, Joachim, succumbs to his illness after leaving and returning to the sanatorium, dying with military discipline and honor. Later, the intellectual rivalry between Settembrini and Naphta culminates tragically in a duel with pistols, which Naphta ends by shooting himself in the head.

The “Thunderbolt” (Departure): Seven years after his arrival, Hans’s stay is abruptly ended by the “Thunderbolt”—the outbreak of World War I. He leaves the sanatorium, descends into the “flatlands,” and is last seen as a soldier caught up in the chaos of battle, his ultimate fate left uncertain.